PRESENCE (ongoing)

“Presence” has a long history in the Western philosophical tradition and is most notably articulated by German philosopher Martin Heidegger. In his work, “presence” denotes our mode of being (as presence-to-the-world) and the mode of being of things (as presence-at-hand). However, “presence” has also taken roots in our everyday discourses: we are present on social media, we hope to be present for our loved ones, but also present, or available to anyone who reaches us through electronic means of communication. On the other hand, “being present” resurfaces as an alternative to busying ourselves with things. Associated with Buddhist practices of meditation, “presence” refers to an increasingly luxurious opportunity to be here and now, to suspend inner narration in order to be an unengaged witness to the world.

In my ongoing project PRESENCE, I explore the topic of self-alienation through technological devices and consumerist culture, in which Buddhism becomes commercialized as a one of the tools to fight anxiety and depression in an existentially challenging world. In other words, Buddhist practices figure as a commodity expected to help us “to be present” in order to remain fully functioning inhabitants of the lifeworld dominated by these self-alienating and consumerist practices.

In PRESENCE I approach this topic through the iconography of the Gandhāra tradition in Buddhist art, which is a form of cultural syncretism between the Ancient Greek art and Buddhism. Given my background in Western art, Gandhāra tradition seems more accessible and understandable to me. Yet it also corresponds to my status of an outsider getting immersed in the lifestyle of Hong Kong as well as to its syncretic culture—a city that is existentially challenging and self-alienating.

In my ongoing project PRESENCE, I explore the topic of self-alienation through technological devices and consumerist culture, in which Buddhism becomes commercialized as a one of the tools to fight anxiety and depression in an existentially challenging world. In other words, Buddhist practices figure as a commodity expected to help us “to be present” in order to remain fully functioning inhabitants of the lifeworld dominated by these self-alienating and consumerist practices.

In PRESENCE I approach this topic through the iconography of the Gandhāra tradition in Buddhist art, which is a form of cultural syncretism between the Ancient Greek art and Buddhism. Given my background in Western art, Gandhāra tradition seems more accessible and understandable to me. Yet it also corresponds to my status of an outsider getting immersed in the lifestyle of Hong Kong as well as to its syncretic culture—a city that is existentially challenging and self-alienating.

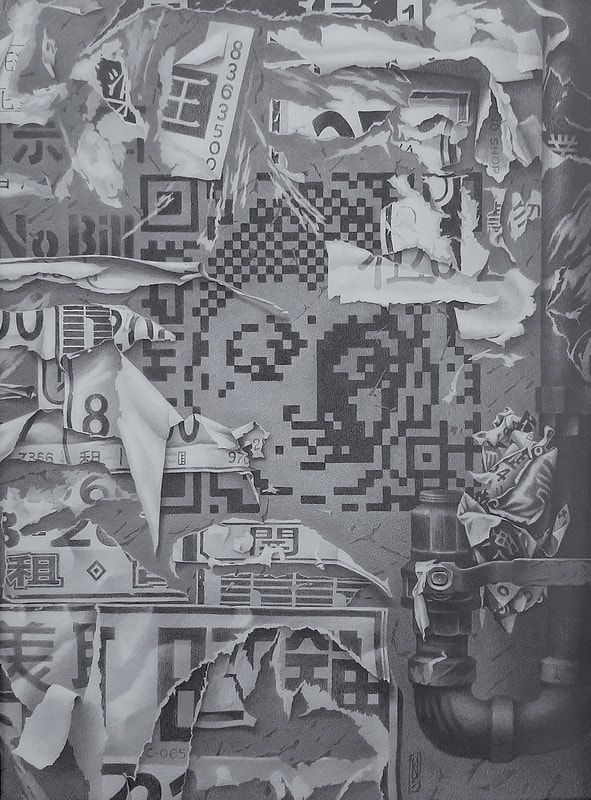

In “Signfulness”, I ponder the process of turning Buddhist practices and concepts into a commodity, a product meant to help currently unfit members of society to re-situate themselves within the habitual contexts of production and consumption. Thus, being present becomes a luxury to pay a high price for. Turned into a QR code and almost lost in scraps of posters advertising the real estate – a commensurable luxury – Buddha’s face competes for one’s attention: “Click here, check your spiritual status, find out how you can be more present…”

“Emptiness” derives its meaning from the Buddhist concept “flowers of emptiness” symbolizing things that we desire and that eventually lead to our suffering. Suffocated by flowers, Buddha mountains his serene expression while indicating the strokes of a character that stands for “Śūnyatā”(空) on his palm. Regional plants are chosen to represent “flowers of emptiness”, namely Bauhinia × blakeana, a sterile tree whose flowers produce no seeds or fruits, and Macaranga tanarius, a usually unnoticed shrub or bushy tree, whose leaves become beautiful and thus noticeable when dead and dry.

“Enlightenment” started as an inquiry into how the imagery of Buddha is constructed by display practices at museums and art galleries. Lit from above, sculptures and reliefs of Buddha present a serene, almost angelic look that comes to our mind when thinking about Buddha. In contrast to it, Buddha’s face lit by the light from below –a typical way in which our faces are lit by smartphone or computer screens– presents a completely unfamiliar look of Buddha. Departing from the intuitive depiction of the enlightened state, I thus contrast the enlightenment as the goal of one’s self-cultivation with its caricature, constructed or offered, as an alternative, by self-alienating sides of technologies.

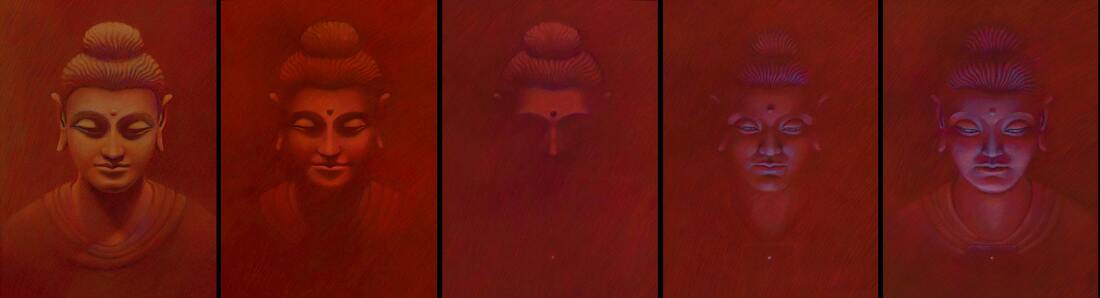

“Illumination” elaborates on the same point as “Enlightenment” by reconstructing, in 5 steps, the transformation of Buddha’s face as it disappears in the dark and reappears lit by cold screen light. On the last step Buddha acquires an almost demonic look, thus mirroring an unflattering, sometimes ugly identity we often assume in an anonymous space of our online presence. Buddha’s face at the beginning of this reconstruction, lit by warm natural light, is the image we strive for or think we have already achieved while being unaware of our demonic side or the ease with which it can be reached.